Source: The New European

Richard Holledge

16.03.2023

PRESS TEXT

The art the Taliban couldn’t stop

Hundreds of Afghan artists have had to flee the country since the regime closed down galleries and threatened them with prison

For centuries, the Afghan city of Herāt was a thriving centre for art and culture. Its artists created exquisite miniatures on silk, and illustrated poems with their tales of courtly love and lustful longings in vivid colours.

Most revered was a Persian painter, Ustād Behzād, (c. 1455-1536) who created an academy that centuries later was reborn as an art centre in an ancient waterworks. Renovated by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, it was named after him when it opened its doors in 2009 to young artists – male and female. Their talents flourished and the gallery walls were alive with works of art.

The Behzād was just one of several galleries in Herāt that thrived until the return to power of the Taliban in 2021, who closed them down and threatened artists with imprisonment and violence. Little wonder, then, that hundreds of artists have fled the country, helped by several charities, to find a new life in European countries such as Sweden, Germany and Finland, as well as the USA.

One of them is Mahsa Falah from Herāt who embodies the spirit, if not the style, of the great Behzād with her range of vigorous landscapes, abstracts and surreal imagery. Only 26, she exemplifies the courage and determination to succeed shown by many of the women faced with the grim misogyny of the Taliban. She studied at the Herāt Faculty of Economics and Management before working in an international trading company supervising more than 100 young women and girls.

In 2018 she fulfilled a dream by founding the MN Fine Art Cottage gallery with her sister. She staged exhibitions, including shows of her own works, and taught poorer students for free – because she did not want them to give up on their dreams. She was interviewed on television about her work and it is clear she is brimming with confidence and delight at her achievement. It was, she says, the best year of her life.

But then the Taliban arrived.

Perhaps it is best to let her tell her story in her own words, because she speaks with candour and passion not just for herself but for all the artists who have been driven out of their homeland. (Few speak English well enough, so interviews were conducted via email or with a translator).

She writes: “I never thought that they (the Taliban) would enter the city until three days before Herāt fell. The whole city was filled with a strange worry. The students became very few and did not come (to the gallery) any more. I went on the last day and sat alone, read a book and returned home – until the next day. At 4.40 in the evening, they entered the city with the sound of cannons and guns.

“My heart trembled lest Herāt fall. I still couldn’t believe it. I was still expecting the news of the defeat of the Taliban. We had a terrible night, the electricity was cut off and we all gathered in a safer house to protect our lives from bullets and rockets. At 8pm I read on the internet that Herāt had fallen into the hands of the Taliban.

“And my whole body trembled and tears flowed. I was talking to myself, what does that mean? Why did it happen? How is it possible? And thousands of other questions. After that day it was as if I and thousands of other Afghan girls died. Really died.”

After enduring five months of Taliban rule she left the country, first for Iran where she worked in a greenhouse, packaging flowers from dawn to dusk. At the end of the day, her hands were scarred by thorns.

But she was one of the luckier ones. After four months she was helped to freedom in Berlin by the charity Artists at Risk (AR).

She recalls: “When I knew I was leaving I went to Herāt for the last time to be with my family on my birthday. It was very hard when I faced my mother’s tears and my father’s tears at the door to say goodbye. But I didn’t let them see my tears. As soon as I got 200 metres away, my anger burst and I cried for miles.”

Stories like Mahsa’s are all too familiar to Artists at Risk, which was set up 10 years ago in Finland by Marita Muukkonen, who has worked in arts administration, and Ivor Stodolsky, from the world of politics and academia.

Their first task is to arrange visas, help with finances and accommodation, and eventually find work for the refugees as well as integrating them into the artistic world and community they have found themselves in. It’s an uphill struggle.

AR started with a list of more than 450 artists desperate to flee Afghanistan, but that figure rose to 2,000 more when families and dependents were included. Now there are 750 more waiting for their help – and that does not include families.

The charity is helped financially by organisations as diverse as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Finland, the Swedish Arts Council, Harvard University and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Some of the money is spent on a safe house in Afghanistan where artists in peril from the Taliban can hide. In Berlin, money goes towards accommodation in a former bathtub factory that is shared by seven Afghanis and three refugees from Ukraine. They have their own bedroom, two shared kitchens, living rooms and a workshop-cum-studio.

The biggest stumbling block to finding them a new home is getting them a visa.

“That is in the gift of the ‘receiving’ countries in the EU and the west,” says Stodolsky. “The problem is that western governments have stopped or stalled the issuing of visas. The German government introduced a new programme and promised to bring 1,000 people out a month at least. They promised that in October, but they haven’t brought a single person out yet.”

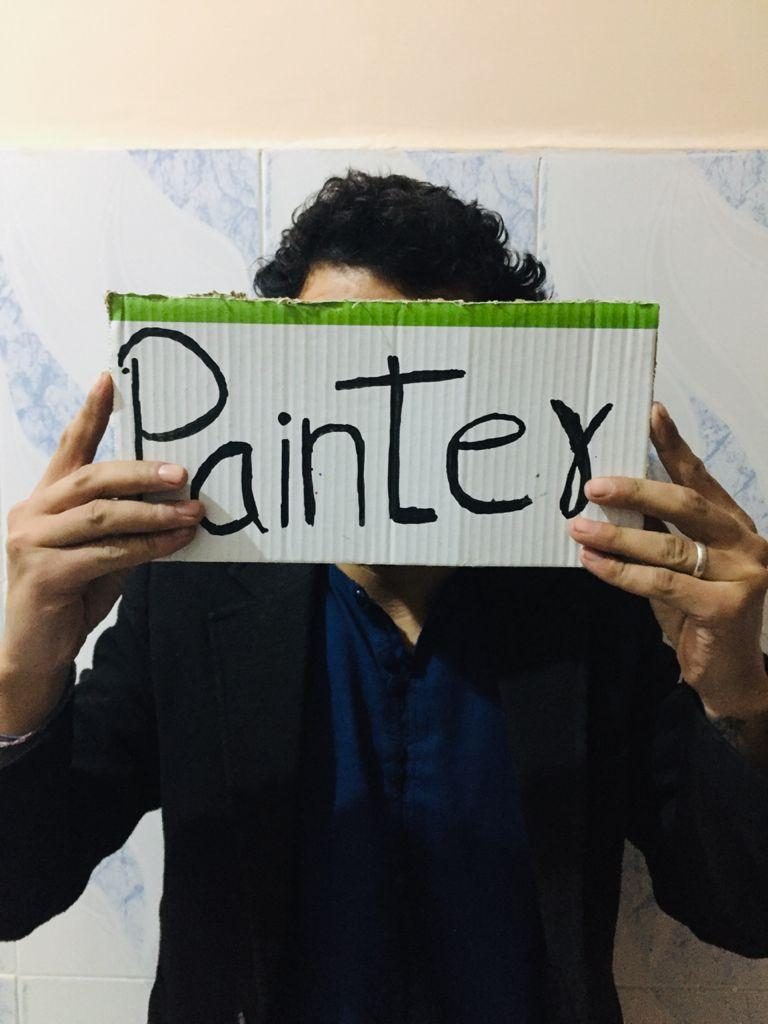

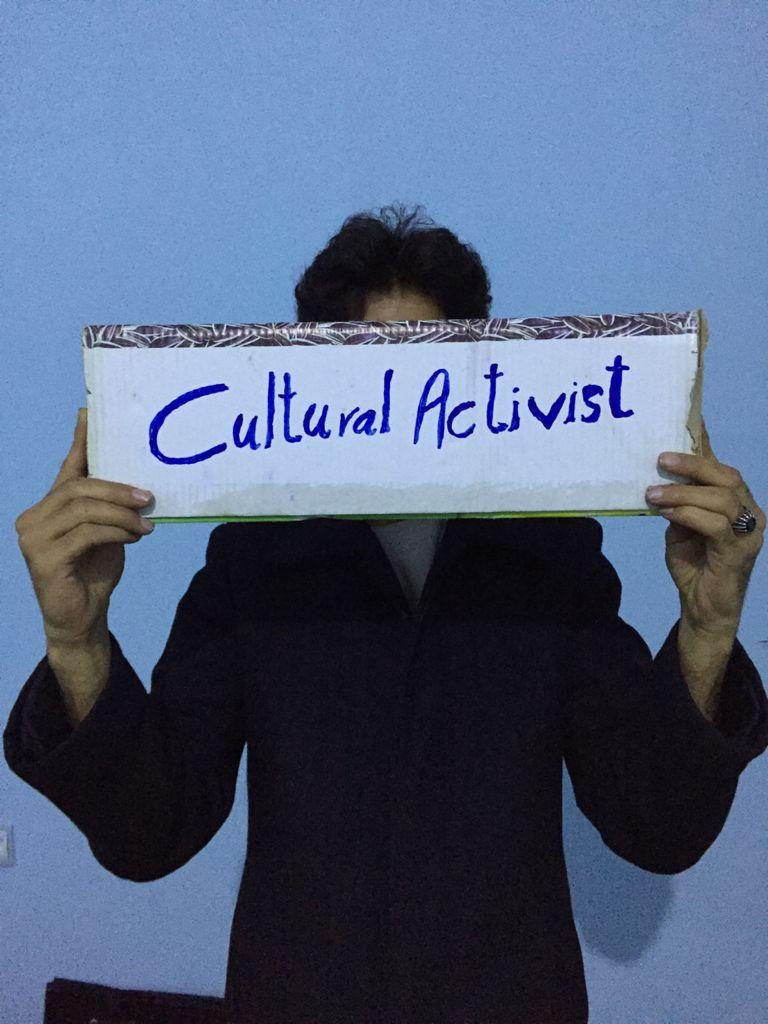

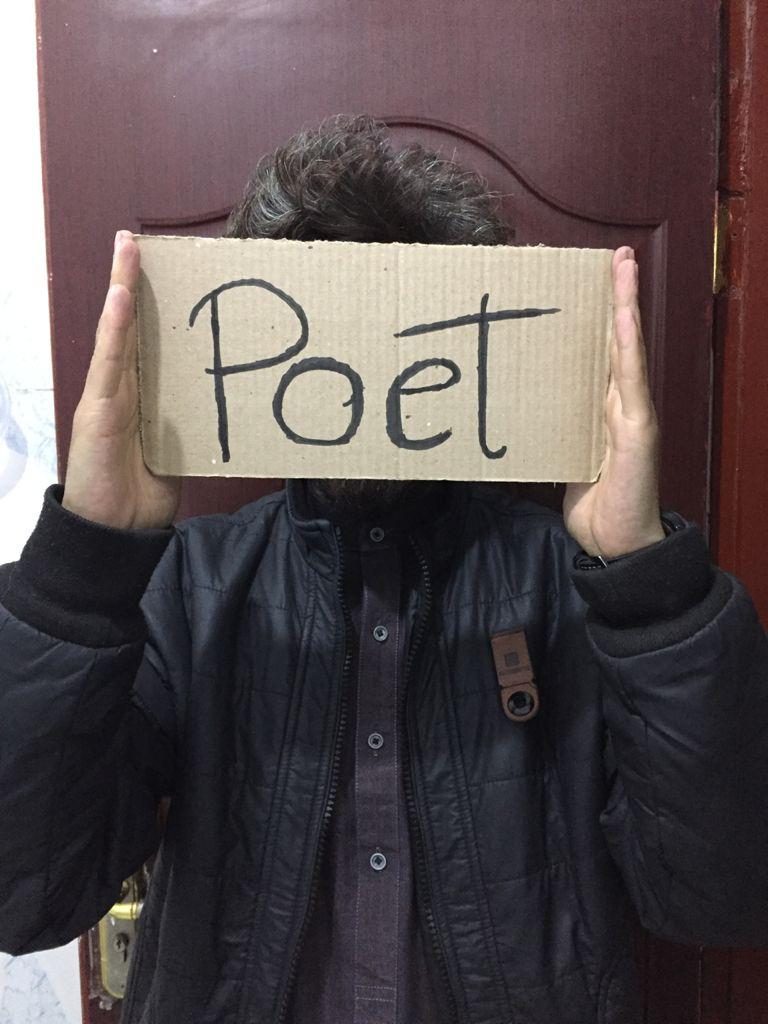

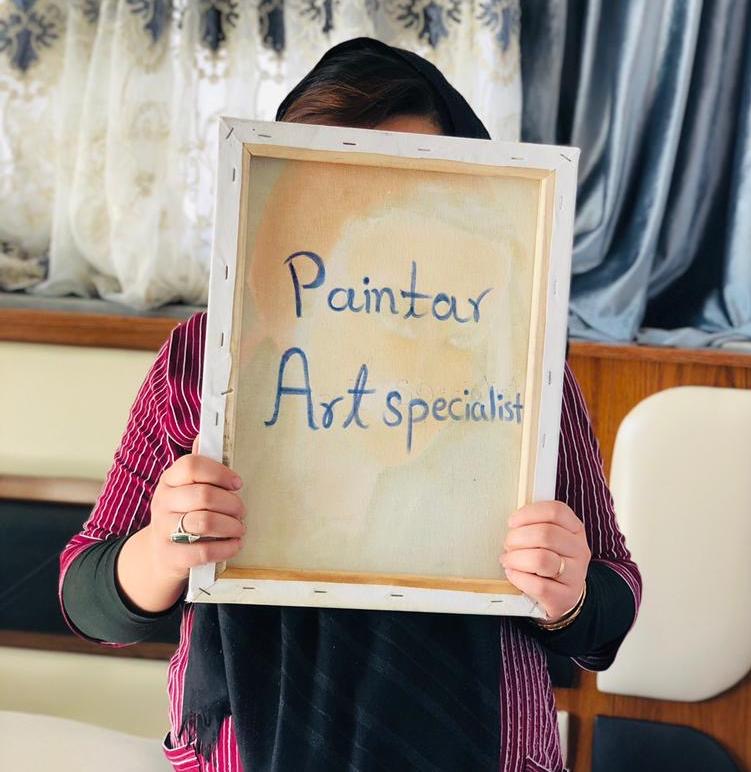

In a striking attempt to shame the west into action over visas, AR arranged an appeal to western heads of state in a letter containing a poster that showed a group of artists in Afghanistan. It was too dangerous to identify themselves so each held a poster in front of their faces with their profession written on it.

It was a desperate plea for freedom, but there is also a nobility about their appeal. The signatories wrote: “We must guarantee that the precious national culture and spirit of the Afghan people remains alive for future generations.”

They begged for the immediate provision of visas and resources to help them escape inevitable Taliban persecution. Sadly, there was no reaction from any politician.

But even when they do reach the safety of the west, a whole new set of challenges has to be met. The language, the traditions, the customs – all alien to them. How can they survive and become independent? How can they be integrated into the artistic world of the new host country and keep their work alive?

AR ensures that artists in the Berlin building are encouraged to stage poetry readings, film screenings and exhibitions, and encourages both artistic and social networks, to create new contacts when they arrive. The charity has introduced artists into international events such as the Istanbul Biennial, as well as shows in Madrid, Athens and Helsinki – which gives them a voice and helps them to continue as professional artists.

Fareba Qasimi, for example, was a daring figure in Kabul where she shocked and delighted audiences in the city by dressing as a boy and performing hip-hop routines. Now the 22-year-old and two other dancers have been taken under the wing of the Centre National de la Danse (CND) in Paris, where they have been given facilities to practise and take part in dance classes.

Mirwais Rekab, 42, won many international awards for his work as a film cameraman before fleeing to Pakistan when the Taliban first banned all cinemas in the 1990s. He returned in 2001 after the liberation of Kabul and established a collective aimed at introducing European new-wave cinema to an eager audience. Once again, the Taliban drove him out.

He is now with his family in Hamburg, where he is working on two documentaries and helping to organise an Afghan film festival.

Iqbal Ahmad Tarnak is struggling because of a problem with his refugee grant that has left him without money and forced him to rely on AR for his subsistence.

He graduated from the fine arts faculty of Kabul University, where his work developed from painting miniatures to contemporary art and on to video and installations. He ran a workshop and was teaching painting and calligraphy to about 200 students when the Taliban ordered him to take down his paintings, threatened him and closed down his workshop.

In an email conversation, he confessed that “migration makes man incomplete”.

“As an artist, being in Afghanistan and having no freedom is like dying. I still feel my soul is in Kabul because when a person is born in a particular place, his spiritual connection is established with the same society, people, culture, soil, and air, and the person feels that his soul is tied to it.”

And he speaks for all the exiled artists. “When you are forced to go thousands of miles away from your homeland, you don’t have friends, you don’t know the language, you don’t know the culture and traditions of that society, and then the new life is naturally more difficult.”

But he will not be defeated. “I am learning the language, studying the culture of this society. I want to learn more about the art.”

He has shown his work in three small exhibitions so far. His paintings are fierce, angry, representations of grotesque creatures and quotidian objects often sporting savage talons, an ugly reflection of how he perceives the Taliban and quite a contrast to the finely wrought miniatures he has crafted in the style of Behzād.

The pain of exile is echoed by Fahim Maroofi, 32, once a professor at the faculty of fine arts at Herāt University, where he taught composition, graphics and design. Now in Michigan, USA, where he is working in a factory making car parts, he writes: “After 20 years, unfortunately, the same bitter and dark times are once more ruling over the people. After the Taliban came, all my achievements and the work of all the artists were lost.”

Maroofi was also an enthusiastic participant in an activist group, the ArtLords, who painted more than 2,000 murals across the country. The works were aimed at shaming corrupt government officials, calling for dialogue instead of violence, and demanding rights for women.

It was ArtLords and its co-founder, Omaid Sharifi, 36, now a fellow at Harvard University, who helped Maroofi to safety along with 46 others.

The artist says: “I still haven’t returned to my normal state and I suffer a lot from the mental point of view, but my effort and motivation is to grow more and serve my people and country, for art and for beauty. I hope I can introduce the authentic arts of Afghanistan to the US, such as traditional tile making, silk weaving and miniatures, calligraphy and music.”

This spirit of defiance, this yearning to keep their own flame of creativity burning, is typical of all the exiles.

Mahsa Falah says: “The bad situation that happened to art and artists, and now all the ways of growth and progress are closed for women and girls of my country, especially the beautiful world of art, which lives in deep darkness and is considered a crime, does not calm me down.”

But such is her determination that she has roused herself to paint and write poetry and she is working on a novel – fittingly – describing the anguish of an Afghan girl whose dreams have been violated.

“My strength and power as an Afghan girl is waiting to flourish again in a different way. I think I still have untouched abilities and talents in me to express,” she says. “Little by little I have found my laughter, my voice, and words rose in finding their way. And my faith has grown again.”