SOURCE: Gagosian

Gillian Jakab

09.06.2020

PRESS TEXT:

THE BIGGER PICTURE

ARTISTS AT RISK

Artists at Risk (AR) is a nonprofit organization that facilitates the secure passage of persecuted artists and welcomes them in safe-haven residencies around the world. But what happens when the world’s borders close due to a pandemic? In mid-May, Gillian Jakab spoke with founders Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky in Berlin and artist Benjamin Abras in Tunis about the history of the organization, the residency experience, and the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund.

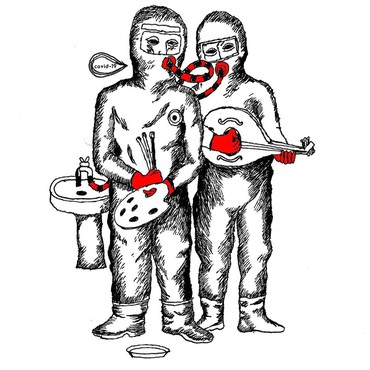

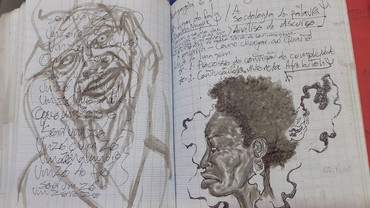

Born in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, Benjamin Abras is a poet, visual artist, actor-dancer, director, essayist, playwright, singer, and composer. Abras looks through the lens of geopoetics to unveil the historical dialogues that make up contemporary identities. In his performance practice, he explores the movement language of Afro Butoh. Photo: Neïs Michel-Casasola

Gillian Jakab is associate editor of the Gagosian Quarterly and, since 2016, has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail.

Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky are co-founding directors of Artists at Risk (AR) and Perpetuum Mobile (PM). Artists at Risk has created more than seventeen safe-haven residencies in fourteen countries since 2013 and has received the Civi Europaeo Praemium of the European Parliament and the Thematic State Prize of Finland, among other honors. Perpetuum Mobile, which operates Artists at Risk, is a curatorial vehicle that brings together art, practice, and inquiry. Photo: Roser Gamonal

GILLIAN JAKAB: Thank you all for taking the time to join me from across the globe. Marita and Ivor, could you start by talking about how you conceived of Artists at Risk? What has your work looked like up until this point of the COVID-19 pandemic?

MARITA MUUKKONEN: We started Artists at Risk in 2013. It grew out of our curatorial and institutional practice. We have worked since 2007 as Perpetuum Mobile (PM), an institution that serves as an umbrella organization for Artists at Risk. We’ve worked a lot with art practice and inquiry, meaning politically and socially engaged art. The first big project we did together as Perpetuum Mobile, The Raw, The Cooked and The Packaged—The Archive of Perestroika Art, was focused on dissident artists from late-Soviet times. That led to another, bigger thematic series in 2011, called Re-Aligned, which grew from all the uprisings and revolutions going on: in Northern Africa, in Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square, in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, in New York with Occupy, in Spain with the Indignados, and so on. Many artists joined these movements. We did fieldwork and met artists and intellectuals who were active participants in them. The project grew, with over ten iterations consisting of exhibitions, public art, workshops, conferences, residencies, and publications.

IVOR STODOLSKY: While we were doing the field research for Re-Aligned, in 2011, we were keenly interested in the revolution that was happening in Egypt at that time. We curated a program in public space for the art organization Checkpoint Helsinki, including on one of the main squares in Helsinki, and invited many of the leading figures in the Egyptian revolution to participate.

At that point, they were able to still travel. This was a kind of in-between moment before the reestablishment of outright dictatorship, as it is now again under [Abdel Fattah] el-Sisi. [Hosni] Mubarak had been deposed, there was the SCAF [Supreme Council of the Armed Forces] regime, then [Mohamed] Morsi. In the beginning, we were connecting with these artists, showing their work, and talking about what it means to go “back to square one” and going “to square two”—that is, starting a second time.

But then the el-Sisi regime cracked down, very harshly. This happened across the region and in other parts of the world, as Marita mentioned. So the initial moment of hope was suppressed, and we realized that the artists we were working with were being put in jail, or threatened with prison, or hounded in other ways, and so we started residencies in which they could take a breather, so to speak, from an oppressive local situation. There were also other vectors of persecution we encountered, of course, related to gender and ethnicity.

MM: At that time, we just provided residencies for artists to get out. We started to map the situation and realized that there’s PEN, which has been working with journalists and writers since 1921, but no organizations dedicated to helping artists from other disciplines. So we started to develop this practice into an institution, with more systematic work. We expanded beyond Helsinki, and other residencies and arts institutions joined to host artists.

IS: The model we developed involves working with local spaces and museums, artists and curators, artist unions and associations, pro bono lawyers, and human rights organizations to provide a rich local network that can work with the very specific needs of each Artists at Risk resident. This way, we also plug artists into the gig scene, the gallery scene, and so on. Artists are now hosted in over seventeen locations in fourteen countries around the world.

Maybe you could talk about your background and experience, Benjamin?

GJ: Yes, I’d love to hear your story.

BENJAMIN ABRAS: I’m an interdisciplinary artist—I use the languages of poetry, music, dance, and visual art in my work. In the risk situation I was in in Brazil, I wasn’t able to produce work as I wanted to. The last work I made there was a performance I directed in 2018. By the time I left, I was in a very difficult, dangerous situation; it was life or death. I ended up going to Portugal, but I wasn’t able to find any support—there were many, many Brazilians seeking political exile in Portugal, trying to escape the government of Jair Bolsonaro—and so I went on to Morocco.

I didn’t really see any possibilities; I didn’t have anybody in Morocco. But two wonderful artist friends, Nastio Mosquito and Jelili Atiku, told me about Artists at Risk. Jelili and I have the same ancestral connection; I’m from the tradition in Brazil called Candomblé, which comes from Nigeria, where Jelili is. We both create contemporary art with that tradition. Nastio was in contact with Marita and Ivor, and they shared the application opportunity with me.

When Marita and Ivor arrived to help me, we found a Gnawa master, Abdellah Elgourd. I spent three months dancing and conducting research about diaspora and the resilience of traditions created in times of slavery, like capoeira and Candomblé in Brazil. Now I feel lucky to be part of another Artists at Risk residency, in Tunis, with support from the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund. I teach dance and theater workshops. I’m writing a book and a play; I’m making new music. It’s not an entirely stable situation, but it’s so much better. I am really happy to be alive and doing what I believe in and speaking freely. The work done by Artists at Risk allows professional artists to keep producing what we do.

BEING IN CONFINEMENT IS A HUGE OPPORTUNITY TO RETHINK THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HUMAN BODY.

Benjamin Abras

GJ: I read that one of your artistic interests is looking at movement and the body in social space—which bodies are restricted and which aren’t. That struck me now, in the context of the pandemic. Social space and bodies are a fraught topic.

BA: Being in confinement is a huge opportunity to rethink the relationships of the human body. I am really thinking about what kind of relationship we have to nature and its vibrations. At the same time, there is a shadowy side to this moment; for example, the increased threat of physical and psychological violence for women locked in with bad partners. It’s a time to put up a different mirror to look at ourselves. How can we rebuild ourselves in this situation, in the face of solitude, of loneliness?

I have started to share the training of capoeira with people through my Instagram, because capoeira was created in jail—in the cage called senzalain the time of slavery. It’s a martial art that was created in lockdown. The epistemology of capoeira comes from looking at the reality you have, to learn how to move through it in a wise way.

GJ: Marita and Ivor, can you tell me about the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund? We’re in this moment where global mobility is halted due to the public health crisis, but people are still in precarious situations and need support. How does this affect the work that Artists at Risk does?

MM: Basically, artists can’t travel. Many governments, like in Brazil, as Benjamin mentioned, are misusing emergency laws to oppress dissidents, intellectuals, and political opposition. That’s the situation many artists are facing; it is quite impossible, too, to find work—to make a living. For dissident artists, it’s difficult even during normal times; now it’s twice as hard. In some cases, police can track where you live and put pressure on you. In other cases, artists simply can’t pay their rent and might face eviction.

With the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund, we want to help artists affected by this crisis, either by moving them to a safer place within the same country or by providing support for their living expenses. We don’t need much to support one artist—for example, in many African countries, it’s three hundred or four hundred euros to cover one art practitioner’s rent and daily living costs for a month. So small donations, in this case, really do make a big difference.

Ivor, do you want to mention the European situation?

YOU’RE UNDER DOUBLE THREAT IF YOU ARE AN ARTIST AT RISK IN THE TIME OF CORONAVIRUS: ON THE ONE HAND, YOU’RE BEING PERSECUTED OR FOLLOWED, ON THE OTHER, YOU’RE A “SITTING DUCK”—YOU CAN’T MOVE.

Ivor Stodolsky

IS: Well, the Schengen zone is basically on lockdown; you can’t even apply for a visa. You’re under double threat if you are an artist at risk in the time of coronavirus: on the one hand, you’re being persecuted or followed, on the other, you’re a “sitting duck”—you can’t move. This is the situation under which we created the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund.

We should remember that there are geographical restrictions on arts funding. In Europe, a lot of funding is from state and local sources, and these are often dedicated to helping local or national or European-level cooperation. However, the funds are not allowed to be spent outside those regions. In fact, we are part of the first funding round of European Union Creative Europe grants in which a North African country, Tunisia, is actually eligible for European cultural grants. But if you happen to be in Morocco, for example, it’s simply not possible.

So these are the kinds of restrictions the AR COVID-19 Emergency Fund was created to get around.

There are other funds that we know how to access as well. Most people in the art world should be able to access funding, but artists at risk often cannot. During the pandemic all artists are at risk, all over the world: their concerts, exhibitions, and dance performances and so on have been canceled. However, non-local artists are often not eligible for emergency state assistance. So we’re fundraising to compensate for that too.

MM: In situations like Benjamin’s and that of his fellow resident at AR-Safe Haven Tunis, Syrian theater director Rémi Sarmini, you need to prove that you have an income to obtain a work-based residency permit. Otherwise, you have to leave the country. In this kind of situation, we have to be able to support people to stay and prove that they have income.

IS: Rémi Sarmini left Damascus just prior to being recruited into the army, where he would have had to either kill or be killed for a system that he opposes. So he escaped to Beirut, and from Beirut to Dubai, then to Sudan, and then from Sudan to Tunis. A remarkably resilient artist, he has now set up a new theater in Tunis with Artists at Risk’s local partner there, ArtVeda and its founder Ahmed Mourad.

As Marita says, for artists like Benjamin and Rémi, you can’t have a visa without an income, and without a visa you have to return “home.” For them, this is not an option.

GJ: Right.

IS: The same is true in Europe. Currently, we have very well-funded residents here in Berlin, for example, through the German Federal Foreign Office. But when the grant comes to an end, they will have to have work to be able to get a so-called Berlin artist visa. If there’s no work, they could be deported.

It’s hard, and many newcomers and artists at risk fall between visa and funding categories.

MM: What is created, during this COVID-19 situation, is an increased connection between artists in different locations. We have been organizing Artists at Risk gatherings online to work together this way. So it’s also good that there are these new practices developing that will last, hopefully, after the pandemic is over.

GJ: Yes, that’s the silver lining; it’s brought up new ways of doing things that might connect you more than if you’re just thinking about physical ways of collaborating.

IS: In the past we’ve organized the Artists at Risk Pavilions—group exhibitions bringing together Artists at Risk residents. Benjamin made work for the latest Artists at Risk Pavilion, in Helsinki: a sound piece with a sculptural aspect. The pavilion is an ongoing format we use, but we’re working in other formats, too, such as music albums.

MM: We’ve recently launched a COVID-19 song by a Somali musician, Lil Baliil, based in Berlin. He released the track in Somali, because there are lots of COVID-19 cases within the Somali diaspora. He’s a pop star; he has many followers in Europe and elsewhere. He won the East African Music Award, for song of the year in 2019.

IS: The coronavirus song is a call for people to respect public health advice, with English subtitles for other communities, like in Kenya, where it was put on national TV.

All the work of AR is made possible through our peer-to-peer network, which means that we all support each other through horizontal solidarity. A great example is in Catalonia, where Kenyan LGBTQI musician Grammo Suspect—one of the first COVID-19 Emergency Fund grantees—was originally an Artists at Risk resident. We’re working with a community of grassroots organizations there.

MM: One of these organizations, No Callarem, just made a generous donation of several thousand euros to our COVID-19 Emergency Fund, which they raised by organizing concerts, selling food, and so on.

BA: It’s wonderful to see that side of Artists at Risk: supporting one another. They care about the human context of art and artists. As a Black artist from Brazil, I talk about racism, violence, and the genocide that is the basis of Brazilian history. As an artist who fights for human rights, it’s wonderful to meet people like Marita and Ivor. Rémi and I don’t know when we can go back to our countries, families, friends, but being here together, we already have a beautiful family with them, with each other, and with all the artists we meet along the way.